Male Amputee Pictures: The Best Resources and Support Groups for Men with Disabilities

- sarasanders97

- Aug 19, 2023

- 7 min read

The publication in spring 1974 of the sad and depressing Australian Survey of Vascular Amputees (Little et al. 1974) disturbed all those involved in the rehabilitation of amputees. Major statistical discrepancies, however, between their findings and those produced for the Scottish Home and Health Department raised doubts as to whether the gloomy Australian picture was mirrored in a more settled European environment. Therefore a survey has been carried out, of a more detailed and comprehensive nature than the above studies, amongst the intake into the Dundee Limb Fitting Centre (DLFC) during the year 1977.

In spite of individual problems, however, the overall picture is bright. Above all the survey underlines the crucial contribution of prosthetic aided mobility to rehabilitation, especially of male amputees.

Male Amputee Pictures

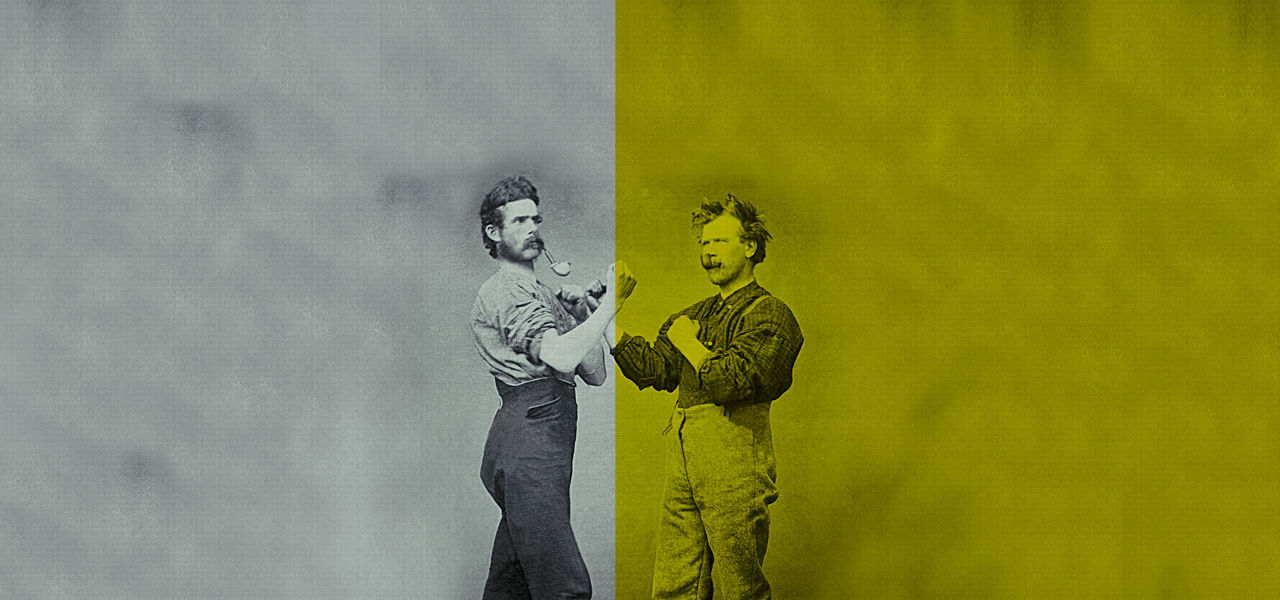

This impressively researched and well written book seeks to fill a glaring hole in Civil War historiography. As historian Brian Craig Miller[1] (Emporia State Univ.) notes, even with the recent emphasis on the darkest aspects of the war, "the consequences of amputation on Civil War soldiers and civilians, both during and after the war, have remained largely unexplored" (3). Empty Sleeves breaks new ground by exploring those consequences specifically for Confederate soldiers[2] and Southern society writ large, with particular attention to the gendered nature of the surgery. Miller argues that amputation not only physically disabled the soldier, but dealt a blow to his masculinity, since Southern men often defined themselves as men by a whole healthy body. Was a man still a man if he was missing an arm or a leg or both? After the war, "Confederate amputees relied solely on themselves, their communities, and eventually their (often dysfunctional) state governments" (4), and asserted their masculinity in a variety of ways.

Empty Sleeves comprises five discrete, roughly chronological chapters on Confederate amputees during and after the war, loosely tied together by the shared topic. Chapter 1, "The Surgeons: Gray Anatomy," focuses on Confederate surgeons, adding to a recent spate of works seeking to rehabilitate the reputation of Civil War surgeons.[3] Miller contends that Confederate doctors were neither heartless butchers nor hapless incompetents, but often skilled and compassionate operators who gained expertise as the war went on. In its later stages, mortality rates declined, as surgeons increasingly practiced safe alternatives to amputation. But growing competence and a will to improve could not overcome the horrific images of their early mistakes.

Chapter 3, "The Women: Reconstructing Confederate Manhood,"[5] is the most interesting and valuable in the book. In it, the author shows that Southern women reacted variously to the return of their disabled menfolk. Some were disgusted by their deformities, while others worried about the financial implications of marriage to an amputee, who struggled financially to provide for his family. But many embraced the damaged men with sympathy or patriotism in their hearts. Most interestingly, Miller identifies a shift in the dynamics of family relationships:

The thorough research for Empty Sleeves took Miller to major universities and archives throughout the South, as well as the National Archives and the National Library of Medicine in Washington. He is also fully conversant with the published primary sources and the pertinent secondary literature on his subject. I do, however, have a few quibbles. While the experience of Union veterans lies outside his purview, the author often paints a too rosy contrasting picture of their postwar lives, no doubt to spotlight the unenviable position of Confederate veterans.[7] In addition, the book sometimes reads like an encyclopedia of Confederate amputees. The flood of case studies at times overwhelms the argument.

This extremely valuable study of the lives of Confederate amputees, the gender implications of their disabilities, and the societal responses to the war wounded is very timely in our own day, when, as Miller notes in his epilogue, more amputees are coming home from America's wars in the Middle East than have since the war in Vietnam. As a fine installment in the "dark turn" trend in Civil War historiography, Empty Sleeves places a salutary emphasis on the lasting, dire physical and psychological effects of war. It is a book that deserves close reading and reflection by academics and general readers concerned with the Civil War, the postwar South, or the history of war-inflicted disability more generally.

[2] On the experience of Union amputees, see Frances M. Clarke, War Stories: Suffering and Sacrifice in the Civil War North (Chicago: U Chicago Pr, 2011), and Brian Matthew Jordan, Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (NY: Liveright, 2014).

This paper deals with the controlling method of A/K prosthesis which enables lower limb amputees to ascend the staircase. As conventional A/K prostheses are designed for walking on the level surface, the disabled persons wearing them have been compelled to walk on stairs with unnatural posture. The construction of powered A/K prostheses requires not only the prosthesis mechanism but also its controlling method. Measuring the axial force and moment acting on the socket that is the human-machine-interface during walking with the six axis force-moment sensor, the torque of disabled side hip joint was calculated. We devised a controlling method using this torque for a feedback signal. The results of clinical walking experiment indicated that the subjects wearing the A/K prosthesis could walk with joint angle patterns similar to those in a normal subject. Furthermore, with the results of the inverse dynamics analysis, the amputee subject generated a torque and power pattern at his disabled side hip joint similar to that in the normal subject.

To disabled persons who lost their lower limbs at the thigh level, A/K prosthesis is an indispensable assistive system for their daily activities. However the function of the conventional A/K prostheses is limited, because they do not enable the amputee to walk on a step or staircase. To solve this problem, the author had developed a multi-functional A/K prostheses. It generated enough power at the knee joint for stair walking(1)(2). This type of powered A/K prosthesis has not been developed with some exceptions. Active artificial Leg was one of them. That had been developed by one of the National Research and Development Programs for Medical and Welfare Apparatus in Japan. The controller of this leg receives signals from a foot-switch equipped in the shoe, and starts extending, the knee joint following a preset angle pattern(3).

In the development of power artificial limbs, not only the development of mechanisms but also the controlling method which drive it adequately are important subjects. Because, if it is not controlled appropriately, the powered A/K prosthesis may injure the amputee or people around him/her with its power. The aim of this study is to construct the new controlling method which has the following function. Amputees can control the movement of their A/K prosthesis by with moving the hip joint of the disabled side same as the normal side, without any special unnatural operation to drive the prosthesis.

Clinical experiments were carried out on two amputees who lost their left thigh. After several trials by them, the trigger torque, MH, that starts the extension of the knee joint was determined to 40[Nm]. This torque is almost equal to that in normal persons. Another trigger compression force, Fz, that starts the flexion of the knee joint was also determined to 100[N]. This force is almost equal o that in normal persons, too.

Figure 4 shows the data on a normal person (left) and these on an amputee (male,aged 27)(right). The upper and lower parts of Fig.4 show the hip joint and knee joint, respectively. The abscissa represents normalized time[%], and 0 and 100[%] mean toe contact. Four domains divided by vertical lines indicate, from left to right, double supported phase, single supported phase, double supported phase and swing phase. The dotted curve and two solid curves show the joint angle, joint torque and joint power, respectively. As to the power curve, the positive value and negative value mean the driving power and breaking power respectively, because the power is a product of torque and angle velocity. These data revealed that the amputee wearing the A/K prosthesis could walk with a joint angle pattern similar to that in the normal subject. Furthermore the results of the inverse dynamics analysis demonstrated that the amputee generated a torque and power pattern at his disabled side hip joint similar to that in the normal subject. Sequential pictures are shown in Figure 5. Within one hour training, the amputees could master stair walking without the help of his upper limbs. A foot switch has often been used as a sensor to generate a controlling trigger signal. However, due to the instability of this signal, the movement of A/K prostheses tends to be unstable. The present study demonstrated that the stability of the A/K prosthesis movement was improved greatly by using the the axial force moment as a controlling signal. In fact, the amputee reported that he felt relieved because when he wanted to move the knee joint of the prosthesis it began moving automatically without any delay.

Wilfred Owen, a Soldier Poet who spent time in several military hospitals after being diagnosed with neurasthenia, wrote the poem "Disabled" while at Craiglockhart Hospital, after meeting Seigfried "Mad Jack" Sassoon. A look at Owen's work shows that all of his famed war poems came after the meeting with Sassoon in August 1917 (Childs 49). In a statement on the effect the Sassoon meeting had on Owen's poetry, Professor Peter Childs explains it was after the late-summer meeting that Owen began to use themes dealing with "breaking bodies and minds, in poems that see soldiers as wretches, ghosts, and sleepers" (49). "Disabled," which Childs lists because of its theme of "physical loss," is interpreted by most critics as a poem that invites the reader to pity the above-knee, double-amputee veteran for the loss of his legs, which Owen depicts as the loss of his life. An analysis of this sort relies heavily on a stereotypical reading of disability, in which "people with disabilities are more dependent, childlike, passive, sensitive, and miserable" than their nondisabled counterparts, and "are depicted as pained by their fate" (Linton, 1998, p. 25). Such a reading disregards not only the subject's social impairment, which is directly addressed by Owen, but it also fails to consider the constructed identity of the subject, as defined by the language of the poem. 2ff7e9595c

Comments